The Wine and the Sponge may sound like a strange title for an article, especially an article on faith, yet we find both items mentioned in the crucifixion account in the Gospels.

As we venture into a sea of sentimentalism, these two items will be our anchors in reality. As humans, we tend to romanticize accounts of our past. Who hasn’t embellished memories from family get-togethers or events that left their impression on our memories? How much more so when it comes to historical accounts that are horrific? Historical accounts are those to which we have a personal attachment or events that profoundly affect our spiritual lives. We are prone to attaching sentiment to symbolic representations of these same events, romanticizing them to the point where the horrific and ugly parts of those events are glossed over or blocked out.

We will consider symbolism while guarding against a descent into idolatry, which happens when we raise the symbol as equal to the event it represents. When this elevation takes place, our focus of worship shifts. If we aren’t careful, we will find ourselves worshiping the symbol more than what it symbolizes.

The other danger of romanticizing past events is that it tends to distort the facts. To avoid this, we will rely on our anchors in reality, the wine and the sponge, to keep us steadfast and avoid drifting into dangerous waters of idolatry.

To Christians, the symbol of the cross is a physical representation of hope, peace, and love, and has since the late 1st or early 2nd century CE. And rightfully so. Jesus’s sacrifice on the cross is the defining moment in human history. For it was on the cross that Jesus offered Himself as the required sinless sacrifice for the sins of humanity. Jesus, knowing payment was made in full, uttered, “It is finished.“

After three days, the world would discover whether God accepted this sacrifice as sufficient payment for man’s sins. And it was. The resurrection was proof of the accepted sacrifice. Thus, the cross became a symbol of victory for all those who believe in Him. The downside of this symbolism is it has given rise to sentiment, allowing us to romanticize the crucifixion and gloss over the horrific abuse Jesus suffered not only on the cross but before it.

We no longer want to associate the cross with the horror and cruelty of the crucifixion of Christ. Instead, we have replaced these thoughts with those of love, warmth, and security. As Christians, we should never forget the death of Jesus on the cross was the ultimate expression of love, yet it shouldn’t veil the fact crucifixion is one of the most brutal ways to put people to death.

Those condemned to die by crucifixion often hung on the cross for hours, enduring the agony of nails in their hands and feet, struggling to breathe. Most times, the victims were left to die on their own, which meant hanging on the cross as long as a full day. At other times, the Roman soldiers would break the legs of the victims to expedite death. The soldiers broke the legs of the victims for two reasons.

One, the victims outnumbered the crosses available. To speed up the process of completing the number of condemned, the soldiers would break the legs of those on the cross so their crosses could be reused on the next criminal.

We find the second reason in the Gospel accounts. The Sanhedrin didn’t think it appropriate for crucified victims to remain on the cross because it would tarnish their celebration of the Passover Sabbath. 1

Public crucifixions also served as a warning to others who committed serious crimes or contemplated challenging Roman authority. It was a successful deterrent. Successful not just because of the death sentence but because of the foreknowledge of the suffering administered before death. Torture, undetermined in length and severity of pain, is displayed in the verbal and physical agony of the victims.

And while the Bible spares us most of the gory details, there is still enough detail to give us a vivid mental image of its cruelty. Romanticizing this event may make it easier for our consciences to bear since it is for our sins and redemption. The wine and the sponge are little details in the crucifixion story that we tend to overlook because they have no place in our romanticized version of the events.

There is nothing pretty about what transpired after the arrest of our Lord. Temple officials brought Jesus unlawfully before an illegal council gathered together by Annas, who was no longer the High Priest. Jesus was then interrogated, mocked, spit upon, beaten, blindfolded, and struck, challenging him to identify his attacker before being sent to the High Priest.

Since only Roman authorities had the right to execution, the Jewish leaders delivered Jesus to the Roman authorities to carry out their dirty work for them, falsely accusing Jesus of sedition against Rome.

The mockings and beatings continued as if it were sport while in the custody of Roman authorities. Jesus was then scourged.2 Whipping His bare back with a multi-tailed whip. A small rock or piece of bone was attached to the end of each tail of the whip, which tore the flesh of the victim. Scourging was so horrific many died from it. But Jesus, surviving all of this, was adorned with a purple robe with a crown of thorns jammed on His head, ridiculing His kingship.

With no sleep, beatings on two occasions, scourging, and mocked by those whom He was doing this for, He is forced to carry part of His cross to the place of execution.

Upon arrival at Golgotha (Aramaic for skull), Jesus is nailed to the cross, all the while being scorned and laughed at right up to death. Roman soldiers gambling for His seamless tunic and other articles of clothing. Imagine hanging on a cross, watching those who nailed you to it casting dice at your feet for clothes they knew you would no longer need. But instead of cursing those who did this, Jesus called upon God to forgive them for what they were doing. It was finished.

A Roman soldier pierced His side, confirming His death. He was removed from the cross and buried in a new tomb, not His tomb, but a tomb belonging to one of His followers. On the third day, He arose from the dead, as foretold, confirming He was the Son of God. By all standards, this portion of the story is a happy one. Victory won. Mentally, we want to rush from the mock trial before the Sanhedrin to the resurrection, allowing sentiment to gloss over the horror of the cross and the physical and emotional abuse before it.

Let’s begin with our Lord’s march to Golgotha to see how far our thoughts of the cross have removed us from its cruelty and hours of suffering. He is forced to carry the top part of His cross from the Fortress of Antonio to the site of the crucifixion, a distance of roughly 2,000 feet.

With Jesus physically unable to continue with the weight of His cross, a Roman soldier compelled Simon to carry it the rest of the way. The street on which this took place is now warmly named Via Dolorosa, Latin for the sorrowful way or way of suffering, which is much more palatable than the literal names.

Previously, I spoke of the dangers of sentiment evolving into romanticizing, and here is an example. The first recorded romanticizing of the cross is a story involving Emperor Constantine’s mother, Helena. Who claimed to have found the cross Jesus was nailed to while touring Jerusalem—the cross, which, according to tradition, was then cut up and dispersed throughout Christendom. The relics were said to have healed many just by their touching.

If the very crucifixion cross of Christ had been kept by the faithful, later to be discovered by Helena -wouldn’t such an essential part of Christian history be preserved intact? Of course, it would. This story of finding ‘the’ cross is fantasy, and it illustrates one of the dangers of romanticizing events. But two seemingly insignificant items recorded in the gospel accounts, the wine and the sponge, return us to the reality of this entire event and quell our romantic fantasy. How so?

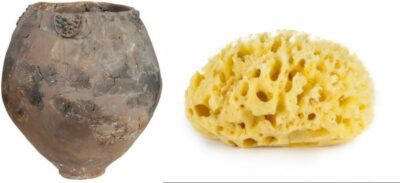

Have you ever wondered how these two items conveniently entered the crucifixion account? Is it at all probable that during this entire event, Roman soldiers would happen upon a jar of wine and a sponge? And what about the reed of Hyssop that the sponge was attached to? Was it lying on the ground somewhere, and a soldier happened to put it to use?

Not a chance. Without the wine and the sponge, our minds are free to romanticize the crucifixion as such– Jesus is marched to a particular pristine location, nailed to a cross which is made explicitly for Him on that day, between two thieves with their specially made crosses, and the location remembered as Calvary, lovingly recalled in hymn stanzas like ‘on a hill far away,’ or in some similar fashion. After Jesus dies, He is buried and resurrected. We have even replaced the word Golgotha with Calvary (Latin for skull), which is not quite as harsh. But then the happenstance of the jars of wine and the sponge.

Their presence punches holes in our fantasy and makes us rethink our mental picture of this event because the wine and the sponge don’t seem to find any place in our romanticized version. We now face the choice of investigating the wine and sponge or glossing over their mention as insignificant. The place of execution, Golgotha, is not a location chosen on a whim. It was a predetermined spot for crucifixions. That’s why we find the wine and the sponge as part of the crucifixion account.

The Romans were highly efficient at crucifixion. Locations readily passed by were chosen for maximum visibility, yet far enough away from the city’s center where the stench of the blood and bodies wouldn’t be a constant bother. It is unlikely the locations selected for public execution would be well-maintained public gathering places. No, places chosen for execution would be places where the stench of bloodshed was irrelevant.

Trained executioners staffing these locations explain why the soldiers gave no thought to gambling for the clothing of Jesus. They were callused men, used to men suffering and dying at their hands, and being soldiers, jars of wine, the typical drink of the day, would naturally be there.

This wine is not the wine we are familiar with; it is a mixture known as Posca (a Latin term meaning a drink). It is a combination of water, wine, and vinegar. In Greek (oxos), this drink means sour wine and is sometimes translated as vinegar since this concoction tasted more like vinegar than wine.

The Gospel accounts mention a second type of wine, which is also present. It was wine laced with a poison administered to the victims by a sponge. This poison (gall) offered to ease the pain and expedite the death of the crucified.

Fulfilling the prophecy in Psalm 69:21, “They also gave me gall for my food and for my thirst they gave me vinegar to drink.” Two different wines, both mentioned in the Gospels.3 The first one, the wine with gall (laced with an opioid, the Greek word chole’), Jesus refused. There would be no avoiding the agony by painkillers or the dulling of the senses impairing His free choice of sacrifice or the taking of poison to expedite death. The only acceptable sacrifice was a sinless sacrifice, and the consuming of any drug would violate His ‘sinless’ condition.

In the psalm quoted above, the term for gall in Hebrew is Rosh (or Rosch). Rosh translates as a bitter, poisonous herb. Sometimes as opium or hemlock. The Greek word chole’ also contains the connotation of a greenish bitter herb, which matches the description of the poppy secretion from which opioids are obtained.4 Rosh or Chloe’ is the gall mentioned in both Psalms and Mathew.

Some may think opium has a recent history. However, there are many historical mentions of opium or opioids in the Middle Bronze Age (2100 BC – 1550 BC). The oldest mention dates back even further, discovered on a Sumerian cuneiform tablet dated 3000 BC.5

The Gospel of Mark introduces another component in the first type of wine (gall): Myrrh.6 The mention of Myrrh in Mark’s account does not contradict the other Gospel accounts, as Myrrh was often added to bitter drinks as a flavor mask. And since the gall mentioned in the Gospel accounts is bitter, adding Myrrh to cut the bitterness makes perfect sense.

We do the same thing today. Children’s oral medications often contain flavors such as grape or cherry to mask the bitterness of the medication. It is also worth noting -both Myrrh and opioids in sufficient quantities are toxic.

The second wine mentioned in the account is the soured wine or vinegar (the Greek word oxos). This sour wine is the vinegar Jesus would taste of, then die.7 As we have already indicated, this is the Posca, the typical drink of the Roman garrisons.

From this additional information, we begin to understand the machine-like efficiency of Roman crucifixion. The location was predetermined – executioners on staff, crosses, nails, wine laced with sedatives, and refreshments for the soldiers. Once the crucifixion victims expired, the soldiers removed the bodies of the victims, and they reused the cross on the next victim.

Wood was and is a precious commodity in the Middle East. So, to think a cross was made for each condemned person is a fantasy. It would be a waste of time and resources. If someone wanted to keep the cross Jesus died on, they would have to buy it from the Roman authorities, which we have no scriptural mention of.

Two other mentions add detail to the scene. First is the reed of Hyssop. Some argue a reed of Hyssop was not rigid enough to support a sponge and would not be long enough to reach the mouth of Jesus. This inference is correct if this was the same type of Hyssop mentioned in Exodus. But there is a variety of Hyssop, which grows in and around rocks and sprouts from the gaps in masonry. We find an example of this type of Hyssop in I Kings 4:33a, “He spoke of trees, from the cedar that is in Lebanon even to the hyssop that grows on the wall;” The last detail we glean from the reed of Hyssop is this. It gives us some insight into the height of the cross.

Art and later in film almost always depict crucifixion crosses as eight feet or more tall. The reed suggests this is not likely. Since the average height of a man in Jesus’s day was 5 foot 6 inches and the length of the reed with a sponge attached approximately 3 feet long, a soldier couldn’t reach the mouth of Jesus on a ten or twelve-foot height cross without using a ladder.

More likely, the cross’s actual height was eight feet, with less than two feet in the ground. This height would put the crucified victim a couple of feet above the ground, and his mouth easily reached with a three-foot reed and sponge.

Every detail in scripture is not superfluous. We have demonstrated how two seemingly insignificant items add great detail to the Gospel accounts of Jesus’s death on the cross. They also can keep us grounded in fact and deter us from romanticizing the horrific and high cost of salvation and redemption.

Death is never pretty; sacrificial death is even more repulsive. But what Christ endured for us that day at Golgotha must be considered with all the seriousness we can muster. A particular cross was never made just for Jesus, nor was He executed at a unique location. No, He was treated and executed like a common criminal in a shared location.

While the symbol of the cross provides peace, details like the wine and the sponge return us to the reality of the great price paid by the sinless Son of God for us. It was for our sins He suffered and died horrifically. Remember, there is nothing wrong with the symbol of the cross being firmly and historically attached to Christianity, but it is just a symbol. It is not to be praised, kissed, or worshiped in any fashion. Recalling the wine and the sponge may help us keep our sentimentalism in check and focus more on the sacrifice made on it.

1John 19:31

2Mathew 19:1

3Mathew 27:34, 48

4Mathew 27:34

5 onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/arcm.12806

6Mark 15:23

7Luke 23:36, John 19:29, Mark 15:36, Mathew 27:48

+ There are no comments

Add yours